Do you have a right to film the police while on duty?

As you know, the video camera is here to stay. With or without audio, police activity can be uploaded to You Tube almost instantaneously. The question becomes one of safety versus a citizen’s right to gather information.

A case in point involved a young lawyer in Boston in 2007. Simon Glik saw three police officers forcing a man to lay face down on a park bench. Concerned that they were using unreasonable force, Glik filmed the incident with his cell phone from ten feet away.

After the suspect was handcuffed, one of the officers told Glik he had taken enough pictures. Glik responded “I am recording this. I saw you punch him.” The officer asked Glik if his cell phone recorded audio and he answered that it did. The officer arrested Glik, placed him in handcuffs and told him he violated a wiretap law, aided in an escape of a prisoner and also was arrested for disorderly conduct.

Police are used to being recorded in the field but many don’t like it. You may have the right to record an arrest or other incident, but law enforcement also has a right to work their case without interference. If told by an officer to stay back or leave the area, it’s advisable to do so.

A balance must be struck between a citizen’s right to know and an officer’s obligation to perform his sworn duty at work. When in doubt, whether the police command is right or wrong, if you pick a fight with someone with a badge and a gun, you’re going to lose. Complaints about rogue cops and police brutality belong to an internal investigation unit, not flashed all over the internet. Most states have laws that criminalize disobeying an order given by a police officer.

Four months after lawyer Glik’s arrest, the criminal charges against him were dismissed. The judge commented that the fact that the “officers were unhappy they were being recorded during an arrest does not make a lawful exercise of a First Amendment right a crime.”

Glik sued the Boston police for violating his freedom of speech and for arresting him without probable cause that he committed a crime. In August, 2011, Glik won. The First Circuit Court of Appeals wrote that “ensuring the public’s right to gather information about their officials not only aids in the uncovering of abuses…but also may have a (beneficial) effect on the functioning of government. . . . We conclude, based on the facts alleged, that Glik was exercising clearly established First Amendment rights in filming the officers in a public space, and that his clearly-established Fourth Amendment rights were violated by his arrest without probable cause.”

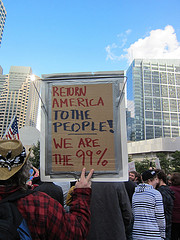

Since roughly 50% of Americans have smart phones, police departments are training officers how to deal with citizen journalists. Many have implemented policies prohibiting the confiscation of cameras and cell phones. Consider the recent Occupy Wall Street protests across the country. In November, 2011, students filmed the pepper spraying of students by the police at UC Davis in California. The officers involved were placed on administrative leave while an investigation into their behavior was conducted. As you can see in the above video, the students were sitting on the ground posing no threat of danger to anyone. Judge for yourself.