The Supreme Court speaks pre-Newtown and Sandy Hook Elementary

The Supreme Court considered a student free speech case in 2007 (Morse v. Frederick) that you may have heard of. It involved a homemade banner created by Joseph Frederick, a senior at Juneau-Douglas High School in Alaska. In January, 2002, the Olympic Torch was passing through Juneau on its way to the winter games in Salt Lake City, Utah. The principal of the school decided to let the students attend the event since it was scheduled to pass the front of the school. She referred to it as a field trip where the school rules would apply. The students were let out of class and they went to the street and across it to watch the Torch go by. Teachers and staff monitored the students during the parade.

Joseph stood across the street and unfurled a 14-foot banner that read “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS.” The principal told him to take it down because, to her, the message promoted illegal drug use. When Frederick didn’t respond, she confiscated it and sent Frederick to her office. He was given a ten-day suspension and later challenged the discipline in court. Five years later the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the school on the basis of the school having a “compelling interest” in drug education and prevention for all of its students.

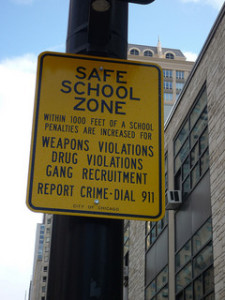

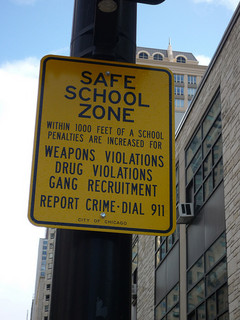

In part of the Frederick decision, Justice Samuel Alito wrote the following about schools and their responsibilities in providing a safe campus for students. Running across this at this time in our history seems particularly poignant. The December 14, 2012 massacre of twenty first-graders and six adults in Connecticut was an unprecedented event in school violence. Hopefully, some good will come from it and Sandy Hook Elementary won’t be forgotten.

“In most settings, the First Amendment strongly limits the government’s ability to suppress speech on the ground that it presents a threat of violence. But due to the special features of the school environment, school officials must have greater authority to intervene before speech leads to violence. And, in most cases, Tinker’s “substantial disruption” standard permits school officials to step in before actual violence erupts.”